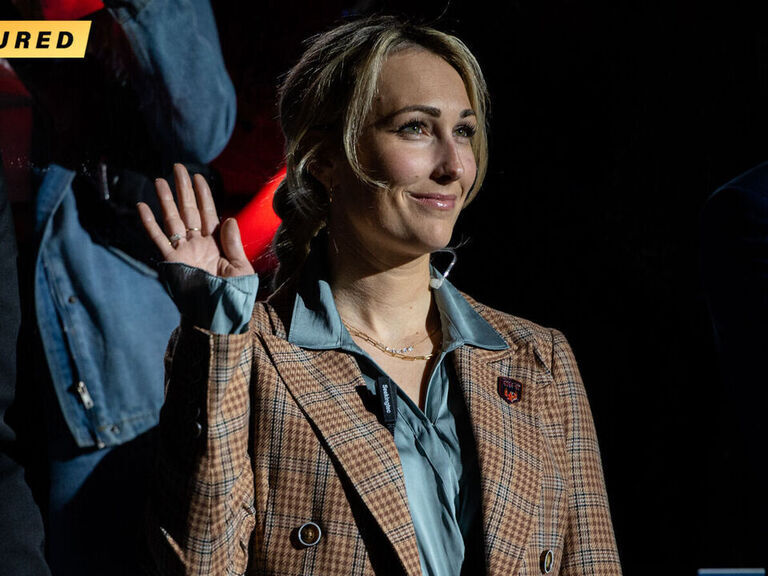

In Jessica Campbell’s rearview mirror, all roads lead back to her 10-year-old self. The first woman to coach full time in the AHL, and one of the first women to work a game behind an NHL bench, Campbell spent the first decade of her life living an idyllic, rural Canadian existence that included hockey, family, and more hockey.

“When she was small we lived miles from town – on a farm – and she would say, ‘Can we go skating tonight?’ and it’d be a blizzard,” Campbell’s mom Monique says. “You could not keep her off the ice. She had so much fun skating with people. She would beg for me to drive her in even though you could barely see the road. That’s how much she loved it, she just couldn’t miss a night.”

Loving hockey was a birthright for the Campbells. As a young adult, Monique played hockey at the University of Saskatchewan, while Jessica’s dad, Gary, grew up on outdoor rinks of Canadian lore.

“It’s something I grew up with, my dad liking hockey so much,” Monique says. “He passed it on in outdoor rinks and small rural teams we got to play on as girls. I got the opportunity (to play) from my dad and my husband got the opportunity from his family. So we just kept that going.”

The four Campbell children followed their parents into a lifelong love affair with the game. Josh, the oldest, had big-league ambitions. By the time he was 17, he was up to nearly a point a game for his AAA team. Next in line was Dion, who played university hockey in New Brunswick before professional stints in the Central Hockey League and in Germany. Jessica’s older sister, Gina, followed in her mother’s footsteps to play university hockey at the University of Regina.

But back in the fall of 2002, when Jessica was 10, the family’s passion for hockey led them to relocate to Melville, Saskatchewan, from nearby Rocanville to be closer to Josh, who signed as a rookie with the Yorkton Terriers of the Saskatchewan Junior Hockey League.

“I want to be a fan favorite here. I don’t just want to be an average hockey player, I want to be one of the best, the best I can be,” Josh said at a press event at the time.

By Canadian Thanksgiving in October, the younger kids were settling into their new schools. Josh, who turned 18 in September, would be heading home for the holiday.

But at 8 a.m. on the Friday of the long weekend, Monique received devastating news: Josh had been in a fatal collision. He wasn’t coming home.

“I remember that morning very clearly. It’s just a heartbreaking, devastating moment. You feel weak and lost,” Monique says.

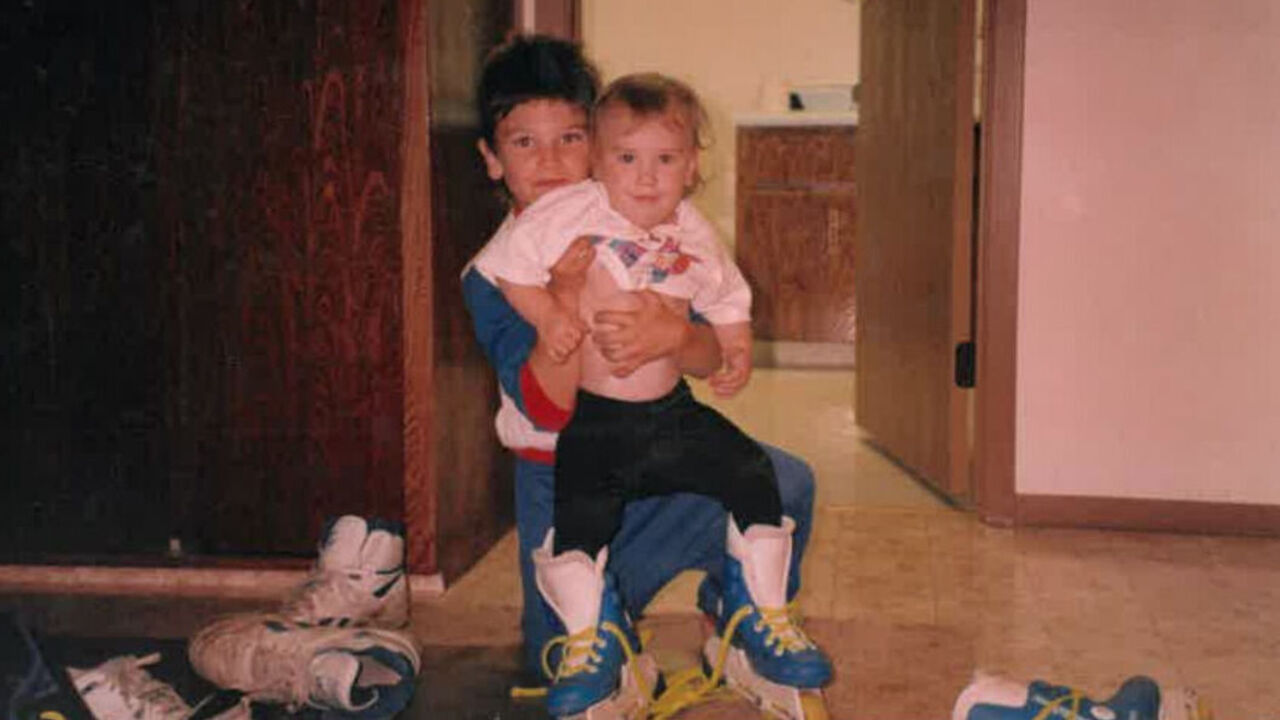

Josh had been Jessica’s biggest role model. “She always connected with him because that’s who we watched play hockey the most,” Monique says. “She looked up to him a lot. He always helped her along the way, giving her tips on the ice, strategy. We went shinnying together and played a lot together. There was a really good bond there.”

The pain pierced through Jessica’s childhood. “Those were hard times on me as a young girl,” Campbell says. The family leaned into what it knew best: hockey. “It was just a challenging time, but I think it only made us stronger,” she says. “And, honestly, it made hockey a place for us where we could work through it. The game itself brought so much joy. I think the game of hockey is an amazing sport because there’s a community of people. When you’re from small towns, that rink, and the arena, it’s a place of gathering where people have each other’s backs and everyone knows each other.”

That community sustained the family through the darkest days following Josh’s death. “A lot of Josh’s friends at the time on the Terriers – his teammates – would come out and watch (Jessica) play. I know that meant a lot to her,” Monique says. “The hockey community – it is like a family, really. They seem to know what you’re going through and are really compassionate.”

As the family adjusted to its loss, hockey helped 10-year-old Jessica define her identity. “The avenue of sport and hockey for me was a place where we healed together as a family but we also could carry on my brother’s love for the game,” she says.

Even before Josh’s death, Campbell had announced herself on the ice.

“I remember I was coaching novice hockey,” family friend Leo Parker says. “We lose to this little novice team. House league teams. We lose, I don’t know, 10-2 or something like that. Jess scored all 10 goals.”

Parker paused to laugh. “My son Andre said to me, ‘Dad, we have to get her on our team.’ She was a perfect little hockey player.”

Following Josh’s death, Parker says Campbell always insisted on wearing his No. 8.

“You can always connect dots back in your life. Right?” Campbell says. “For me, that loss at such a young age and not really understanding why – you never understand why – that was always the driving force for me in my playing career.”

Her goals crystallized in those years: get to the highest level of hockey. As a young woman in the early 2000s, that meant making the Canadian national team. And she had a skill that gave her an edge: skating.

“Jess was always, by far, the best skater on our team,” says Bailey Bram, who represented Canada at the 2018 Winter Olympics. “When it came to power skating drills, she was always the one who the coach was like, ‘OK, Jess, you demo because you can do it best.’ No one would ever race her to anything because it was just like, ‘Jess is automatically going to win.'”

Campbell earned a silver medal at the world under-18 championship and gold the following year as team captain before playing four years of hockey at Cornell. After being cut three times in the final round of tryouts for the senior national team, Campbell was eventually named to the team in 2014, on Oct. 11 – exactly 12 years to the day of Josh’s death.

“She called me the minute she found out. She was just sobbing,” Bram says. “She was just like, ‘This is supposed to happen this way. And it was supposed to happen this weekend.'”

That same year, Campbell signed with the Calgary Inferno in the Canadian Women’s Hockey League, playing with them for three seasons. As her playing career began winding down, it was time for her to ask: what next?

The answer was obvious to the people who knew Campbell best.

From her mom’s perspective, it was natural Campbell would continue to leverage her high energy and love for people. “Jess was a high-spirited child who liked to do everything. She never missed anything. She wanted to be part of a lot of things,” Monique says. Campbell loved hockey’s team atmosphere; even when she was regularly the only girl on her minor hockey team, her mom noticed she formed instant, close bonds with all her teammates on road trips, at tournaments, and on the ice. Her mom couldn’t imagine her doing anything but being involved with a team.

To Bram, skating definitely had to be part of Campbell’s future. “We all thought she might end up doing something with hockey and skating because that’s what she was so good at.”

Putting those two together meant Campbell would be a natural fit to coach, so she took a position in the Okanagan Valley in British Columbia coaching high school girls. Several years into her tenure, she called Bram from a Starbucks drive-through for an impromptu heart-to-heart.

“She said, ‘I’m not unhappy here. I just feel like I’m not fulfilled. I love the girls. They’re fun. But, I just feel I have more potential,'” Bram remembers.

“I wanted to continue to aspire to work with players of the highest level, regardless of gender,” Campbell says.

To aim for the highest levels of professional coaching meant she would have to do something that hadn’t yet been done by a woman: rise through the ranks of men’s professional hockey and into the NHL.

“There is no true blueprint for anybody’s pathway,” Campbell, 31, says. “If you would have looked at mine, you probably would never have said, ‘She’s going to coach in the NHL or be in this position.’ Because the reality was, nobody else was doing it. But looking back now, I feel if I connect my dots backwards, my upbringing and my story as a young girl with the boys has set me up for the right mentality,” she says.

Campbell headed directly from the drive-through to her employer to give notice she was leaving. She had a plan: to launch her own power skating business. And that business took off.

Campbell briefly relocated to Sweden to launch JC Powerskating before returning to the Okanagan shortly before the NHL’s 2020 playoff bubble was set to begin. At the time, many players were isolating in the Okanagan and looking for summer ice to brush off pandemic cobwebs, and before long, she was running 20-person skates with players like Luke Schenn – who won the Stanley Cup with the Tampa Bay Lightning that year.

“I wasn’t focused on trying to get to work with NHL players,” Campbell says. “I was presented with an opportunity where one NHL player wanted ice time and asked if they could come skate with me. Next thing you know, there were 15 guys and I was running an entire NHL group. The realization for me was just to continue to bring that passion and not worry about any of the other barriers or perspectives that others may have about it.”

After noticing her skates gaining momentum with NHLers, Brent Seabrook hired Campbell privately to help him recover from hip and shoulder surgery.

“I really hated her, to be honest,” Seabrook says laughing. He clarifies: “I hated watching her skate.

“I’ll never forget, we were working on pivots. And she’s like, ‘Hey, I want you to come up. And I want you to do like this.'”

Campbell demonstrated the skill and Seabrook shook his head.

“I’m like, ‘Jess, there’s no chance I’m going to be able to get that low and get my leg out that far. And then push and pump. It doesn’t matter how healthy I am or how young I ever was. There’s no way I can get down that low,'” he says. “She was very good with the technical parts of it.”

Her sheer skill earned her respect. “Everything she was asking us to do, she could do,” he says. “Everything. She did it, and she did it really well.

“I find the people that I’ve worked with (who) are really exceptional at what they do are the people that really stop you and correct you and make sure you’re doing it properly.”

But it wasn’t only Campbell’s skating that Seabrook liked; her demeanor was great, too. “She took the time to talk to us. It wasn’t barking. I could talk to her. She’d follow up with questions. She was learning from us as well. She didn’t take any crap from us. She was out there to do a job, and the mentality was, ‘Let’s do it properly.’

“Whatever level you’re at, you want to feel like (your coaches) care,” Seabrook says. “She would go the extra mile. She would text me after to see how I was feeling. Is it too much? What do you want to do tomorrow for the skate? Do you think we should go harder? Should we pull back a bit? There was a plan behind every skate. She cared.”

That’s Campbell’s personality – on and off the ice. “That’s a big piece of who I am as a coach,” she says. “I want to be a coach who is willing to ask the hard questions and who is willing to be sensitive. I know that is my feminine self that comes through in coaching. It is that communication piece. That level of care. Making sure the guys know my coaching style is to lead with love and lead with service for them. Making sure they know I’m in the trenches with them, and all I want to do is see them succeed.”

Opportunity knocked as her coaching reputation grew. In 2021, she headed to Germany to be an assistant coach of the Nuremberg Ice Tigers in the DEL under Tom Rowe, the former Florida Panthers general manager and head coach. After the season, she and Rowe were assistants to Toni Soderholm with the German national team at the men’s world championship.

That’s where Campbell came to the attention of Dan Bylsma, the 2011 NHL coach of the year and winner of the 2009 Stanley Cup with the Pittsburgh Penguins. When Bylsma met Campbell, he was an assistant coach with Team USA, and was also scouting upcoming additions for his staff, as he was set to start as head coach of the Seattle Kraken’s AHL affiliate, the newly formed Coachella Valley Firebirds.

“I started my search with a couple of different names in mind. But I saw her coaching the German national team and I started an investigation into where Jessica was at and where her coaching path was at,” Bylsma says.

He was even more impressed when he learned about her skates in the Okanagan. “NHL players reached out to her and asked her to put them on the ice and through the paces to keep their game fresh and relevant,” he says. “That struck a big chord with me in terms of what kind of coach she is. She can put a player on a path to be relevant.”

When Bylsma hired her, she became the first woman to have a full-time coaching position in the AHL. Now in her second season on Bylsma’s staff and with an NHL preseason game under her belt, she’s close to the pinnacle she sought when she left her high school job.

“I think that my hardships and the challenging times in my life were actually the days that prepared me for the work in this job,” Campbell says. “There are a lot of hard days, there are a lot of sleepless nights. And, I am alone in this space. As much as I feel completely supported by my staff, by Bylsma, by the organization, by the Kraken – everybody has been so supportive of me – there isn’t another female coach specifically in my position that I can call at the end of the day and just communicate with on that same level.

“I think the strength comes from some of the challenging times in my life where I can lean in. I can dig in and access the place of strength.”

Campbell’s in charge of the Firebirds’ forwards and power-play unit. In her first season, Coachella Valley was the AHL’s third-highest scoring team, with 257 goals. The power play hummed at 20.3% efficiency. The club marched to the Calder Cup final, eventually losing to the Hershey Bears in seven games.

Along the way, Campbell did exactly what Bylsma thought she would: show players how to become relevant. She helped transform forward Tye Kartye’s play and jumpstart his NHL prospects. Kartye, an undrafted free agent, led AHL rookies with 57 points in 2022-23 and was named the league’s top freshman. He was called up to the Kraken for the 2023 NHL playoffs.

Kartye’s experience was similar to the one Seabrook had back in Campbell’s early Okanagan days. “She was really good at telling you how the game went and what you needed to improve on,” Kartye says. “Little conversations like that, when you talk one-on-one about how you’re doing and how you can improve and how the games have been going, conversations like that build a lot of trust.”

It’s an approach that proves itself in the details and the staggering amount of hours she devotes to developing players.

“Last year, I was a rookie. I came in and it was a bit of a slow start,” Kartye says. “Being able to work with her after practice – she was always out on the ice before or after practice – whenever I needed to do something, she was always there. She’d pass pucks, give advice, go over video. She helped me an incredible amount as I was trying to reach my goal to get to the NHL.”

Campbell traces that dedication back to her brother. “That mindset of really not holding back and just going for it has always been inspired by my brother and the way he lived and in the athlete and person that he was,” she says.

That work ethic and people-centered approach keep providing her chances to see her brother’s dream come to fruition. “I think every day about how I get to live out my brother’s dream of working or playing at the highest level on the men’s side. I do feel a sense of pride and honor with my family that they get to also experience this with me, and there’s just so much joy around the game. The game has always been a place where we, as a family, have been able to connect and celebrate.”

If Campbell could say one thing to Josh, knowing what she now does about her career path, and her future dreams, she knows what those words would be: “I’m here because of you. And I definitely am grateful every day. I’m never going to take the opportunity for granted to get to do what I love on the ice.”

And if Josh could see Jessica now, Monique thinks he’d use her nickname, one he gave his little sister because she ran before she could walk. She thinks he’d say something like this:

“Boof, we always knew you were going to go far with hockey. Look what you’ve done. I’m extremely proud.”

Jolene Latimer is a feature writer at theScore.