Rarely is fact larger than film. But the real-life Ogie Ogilthorpe was even wilder than his onscreen avatar. Now 69, Bill Goldthorpe is still brawling his way through life 45 years after being immortalized in Slap Shot.

John Rosengren featured the man who suited up for 14 minor-pro and WHA teams in The Goalie Issue of The Hockey News magazine. It’s available for free with a new subscription at THN.com/free.

No doubt you remember Ogie Ogilthorpe, the big-haired goon immortalized in Slap Shot. He inspired lines like, “He is a criminal element, the worst goon in hockey today!” and “For the sake of the game, they oughta throw him in San Quentin!” When Ogie’s introduced, the Charlestown Chiefs’ goaltender remarks with grave concern, “I thought he was banned for life!” Ogilthorpe is the kind of character who makes an indelible impression.

He came to life through the imagination of Nancy Dowd, who wrote the Slap Shot screenplay. The character was based on a man she never met, but Dowd didn’t have to. The stories about the player who inspired Ogie were plentiful enough for her to shape one of the sport’s most memorable anti-heroes. Like the tale about the time when, as a 17-year-old junior player, he beat up one of his own teammates at the airport in Green Bay, Wis. His team left him in jail when it headed to Canada for its next game. Canadian border control would not allow him into his home country for 24 hours, until his Green Bay jailers completed the proper paperwork.

That led to his classic introduction in Slap Shot, the Chiefs’ broadcaster saying, “This young man has had a very trying rookie season, what with the litigation, the notoriety, his subsequent deportation to Canada and that country’s refusal to accept him…Ogie Ogilthorpe!”

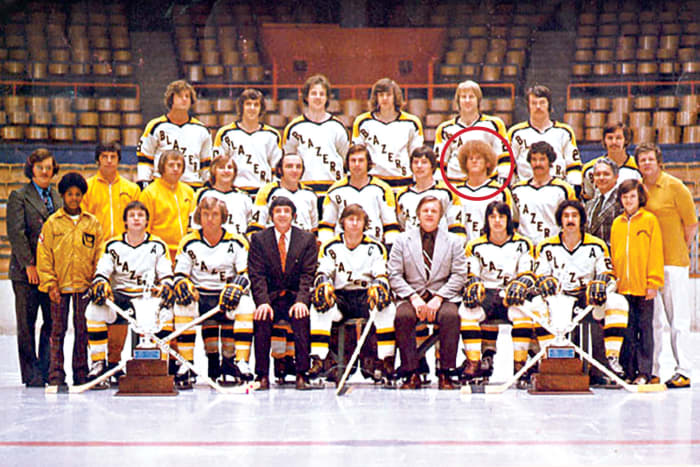

In real life, Ogie is played by Bill Goldthorpe, who “might have been either the wildest or most colorful man ever to play the game,” as Stan Fischler wrote in More Bad Boys. With his signature bleached blond afro, ‘Goldie’ played for 10 minor-league teams and four WHA clubs between 1973-74 and 1978-79, racking up 1,132 penalty minutes in 194 games. Six pro leagues and three senior leagues suspended him. The North American League (the basis of the Federal League in Slap Shot) banned him outright. Off the ice, he racked up at least 30 jailings and countless more fights.

As you can imagine, there are plenty of stories behind those statistics, some that made it into the movie. But the best ones come straight from the source, Goldthorpe himself. At 69, Goldie – as he’s known – was happy to reminisce on the 45th anniversary of the film’s release. “One of the better brawls we had was in Johnstown, Pa., which was the home of the Chiefs in Slap Shot,” Goldie began.

Late in the 1973-74 season, his team, the Syracuse Blazers, had picked up 6-foot-5 Bart Buetow, who’d played college hockey at the University of Minnesota and moonlighted as a lineman in the NFL. After a line fight, Goldie and Buetow wound up in the penalty box with the opposing Johnstown fans haranguing them. “Buetow said, ‘You know what I hate more than the other players?’ ” Goldie recalled. “ ‘The fans.’ He picked one out of the stands and started giving it to him.”

Insanely incited, more drunken fans tumbled over the plexiglass into the penalty box to attack the attackers. Goldie and Buetow fought their way out of the box and back into the dressing room, with the rest of the team, where they then barricaded themselves behind the door. Police finally arrived with dogs to control the mob.

You may recall a variation on this scene in Slap Shot. In Goldie’s telling, the fight, which happened during the second period, so enraged the crowd and endangered the players that the police had to smuggle the team out of the arena mid-game to their bus waiting out back. “The coach looks around and says, ‘Where’s Costas?’ ” Goldie said.

Young Bob Costas, a senior at the University of Syracuse, was working as the team’s radio broadcaster at the time. “He’s up in the press box saying, ‘The players will be back on the ice any time now,’ stalling for half an hour to give us time to make our escape,” Goldie said.

Costas finally joined the team on the bus. By that time, loads of riled fans had swarmed the parking lot. They rocked the bus, and one of them heaved a brick that crashed through one of the vehicle’s windows. “We only got out of town with a police escort,” Goldie said.

Another time that season, in Rochester, N.Y., a fight on the ice spilled over into the hallway. Goldie got arrested along with four other players. The police marched them into the paddy wagon in their full gear – an image you may also remember from Slap Shot.

Even back in the rough and nearly unregulated days of the 1970s, when old-time hockey featured bench-clearing brawls and fisticuffs with fans, Goldie stood out as a guy ready to go, quick to anger – and often quicker to drop an adversary. He battled not only opponents, fans and teammates, but he also brawled with state troopers, busted up a security guard’s dentures, hit an official and more more.

Before he was an enforcer on the ice, he was an enforcer off it, a tough kid from the railroad town of Hornepayne in Northern Ontario. At a minor-hockey tournament, he jumped into a tussle between a man and a referee who’d taken a swipe at a spectator. The man, Albert Cava, turned out to be the coach of the Thunder Bay Vulcans, who later offered Goldie a spot on his team. His role was clear.

But sometimes his extracurricular fights jeopardized his hockey career. Before his sophomore season playing junior in Thunder Bay, Goldie got into a fight with five guys back in Hornepayne, some “druggies” who were “making fun of me.” They didn’t stand a chance. “I smoked them all,” he said in Liam Maguire’s biography The Real Ogie! The Life and Legend of Goldie Goldthorpe. Goldie was charged with five counts of assault and sentenced to serve 15 days for each – 75 total in a town almost 500 miles away from Thunder Bay.

At the time, Goldie was already serving a suspension for hitting a linesman during a fight the previous season. A friend’s father managed to pull some strings and get Goldie transferred to the Thunder Bay correctional facility so that he’d be able to play for the team once his suspension ended. “Buddies picked me up from jail for games and practices,” Goldie said.

If jails had loyalty reward programs, Goldie would have earned preferred status. He was arrested on almost 50 occasions and jailed “easy 30 times” by his own count. Not long ago, a friend designed a T-shirt with Goldie’s angry mug on the front and on the back, under the heading, “The Bill Goldthorpe North American Jail Tour,” a list of 18 cities and dates where he had been locked up. “Every place I played I got put in jail,” Goldie said, “except Minnesota.” There he played three playoff games with the St. Paul Fighting Saints in 1974 – and fought in each one.

Why didn’t he get arrested in St. Paul? “I never got in any bar fights,” he said. “Every other place I played, I have been in bar fights. People come up to you and say, ‘You can’t be that tough,’ and before you know it, you’re into it.”

That must’ve happened a lot, because by his own estimate, Goldie has tallied 500 fights off the ice. Some were more dangerous than others, including the time a drug dealer shot him in the gut and another when a man at a beach cut him up bad with a knife (more on those incidents in a bit). “I was really aggressive when I was younger,” he said. “I probably stepped on a lot of toes.”

But his biggest regret? A goal he didn’t score.

In 1973-74, his first season playing for the Syracuse Blazers, Goldie was a 20-year-old left winger who would go on to score a career-high 20 goals and notch 46 points in 55 games (in addition to 287 PIM). But with his team on a 10-game winning streak to start the season, he tried to go top shelf into a wide-open net – the goalie hopelessly out of position.

Goldthorpe wanted to be more than a goon. He scored 20 goaled in 55 games one season with the Syracuse Blazers.

Courtesy of Liam Maguire and Bill Goldthorpe

“All I had to do was slide it in, but I wanted to put it high,” Goldie said. “I wanted to be one of the boys with this big shot, but I missed over the net.”

His hubris came back to bite him. The game finished in a 3-3 tie and ended the winning streak. “My goal would’ve won the game,” he said ruefully. “I could’ve been the hero.”

Goldie also wishes he’d gotten a shot at the NHL. He came close in 1976, when he was invited to the Toronto Maple Leafs’ training camp, where he played in two exhibition games. They wanted to send him to their Central League affiliate in Dallas, but he refused to go without a contract. They balked, he walked. “I wish I’d gone down to Dallas and worked my way up,” he said.

One time, he was arrested on the ice for an off-ice offense. He was working at a hockey school in Binghamton, N.Y., instructing some kids, when the local police showed up and hauled him in for a slew of unpaid parking tickets. Goldie appeared before the judge in his hockey pants, jersey and tennis shoes.

“I told him I used to take the parking tickets off the windshield and sign autographs on the back for kids,” Goldie said. “The judge laughed and said, ‘I don’t believe it,’ but he let me off for $80.”

Goldie is proudest of the fact that he didn’t back down from fights, on or off the ice, at home or away. “If you just fought at home, you were called a homer,” he said. “I’d rather fight on the road than in my own building, you get more respect that way. I’m proud of the way I played as a tough guy.”

Goldie’s second-most prolific season, both in goals (13) and penalty minutes (267), came over 39 games in 1978-79 with the San Diego Hawks of the Pacific League. He played 12 games the following season with the Spokane Flyers in the Western International League before getting kicked off the team for assaulting the owner, who was upset with him for kneeing an opponent and getting suspended. Goldie returned to San Diego, where an off-ice altercation nearly left him dead.

In the summer of 1980, upset with a drug dealer for messing up his ex-girlfriend with cocaine, Goldie showed up at the dealer’s house one afternoon. “The guy mouthed off, I pushed him down,” Goldie said. “He pulled out a .22 (caliber handgun). I kicked it out of his hand and threw him down. I tried to take the girl out the door. The guy picked up his gun and shot me in the stomach.”

The bullet narrowly missed his kidney but lacerated his urinary tract and destroyed seven inches of his small intestine. Goldie spent five weeks in the hospital, and it took another two years before he could play hockey again. His 58-year-old father came down to San Diego to spend those five weeks by his side, but the stress undid him. Two weeks after he returned to Ontario, Goldie’s dad had a heart attack and died.

“That was a wake-up moment for me,” Goldie said.

You think it might have been the a-ha moment when he got clean and quit fighting. But no. He explains simply, “I never talked to that girl again.”

Goldie did enroll in community college to study computer programming, but the following year, while he was still recovering from being shot, he got into another near-fatal fight. He was walking along Mission Beach in San Diego when he came across a small crowd gathered around a van. Inside the van, a man was beating up a woman. She screamed, but nobody stepped in to help. So Goldie did.

He dragged the man out of the van and had him down on the ground, when the woman stumbled out and accidentally knocked over Goldie, who struck his head, leaving him dazed for a moment. The man fled to his van. Goldie scrambled to his feet and followed. The man grabbed a buck knife off the dash and sliced Goldie in the triceps. Goldie blocked a second blow – aimed at his chest – with his forearm, then managed to grab the man’s wrist and punch him in the face, splitting his skin above the eye.

“He went down but bounced right back up and ran away,” Goldie said. “The cops told me later he was on angel dust, that I was lucky to be alive.”

After taking four years away from the game to recover from his injuries, Goldie made his comeback in 1983-84 with a senior team in Riverview, N.B., where fighting was the main attraction, and his name topped the fight card. The senior team drew better than the Edmonton Oilers’ AHL team across town, the Moncton Alpines. Wanting to boost his team’s attendance, the Alpines’ coach, Doug Messier (Mark’s dad), recruited Goldie.

By then, Goldie had taken up bodybuilding and remade himself into a 216-pound mass of muscle. Underscored, of course, by his reputation. His tenure with the team lasted one game – cut short by a bout with pneumonia – but that was all it took for him to make a lasting impression and further burnish his legacy.

That night, the Alpines faced the Montreal Canadiens’ affiliate, the Nova Scotia Voyageurs, who had pounded them in their previous meeting. Before the game even began, Goldie told one of his teammates to open the bench gate. “They’re playing the anthem,” the teammate protested. Goldie persisted. Soon he was on the ice and jawing at the Halifax players in front of their bench. “I don’t think those Halifax guys threw a hit all game,” the teammate later told the Globe and Mail.

Goldie returned to the Riverview senior team for the Allan Cup playoffs. When an opponent high-sticked him, Goldie hit the guy back so hard he broke his own stick. He was suspended the rest of the playoffs. As it turns out, that was his final act employed by a hockey team. By age 31, all of the hits had taken their toll. “I got tired of fighting,” he said.

Goldie found work doing construction. And he threw himself into bodybuilding, winning the Mr. New Brunswick title in 1985. These days, he still lifts weights, but not for show, simply to stay fit. His competitive days are long past, and he hasn’t skated since 1992, when he played in a tournament. But nearing his 70s, and now living in Surrey, B.C., where he works as a foreman for a Vancouver-

based construction company that builds commercial properties, Goldie still has that chip on his shoulder.

He may have wearied of fighting on the ice, but he has continued to throw punches at anyone who looks at him cross-eyed, makes a wise comment or otherwise gets under his skin. Some things just don’t seem to change.

Last time he was in a fight? About a year ago. “This young guy from Quebec who sold drugs, there are a lot of drugs in construction, thought he was a tough guy,” Goldie said. “At 6:00 a.m. he started mouthing off, so I got up and dropped him. I got fired.”

Goldie would’ve made the perfect Ogie, but he never got the chance to play him. Instead, the part went to Nancy Dowd’s brother Ned, who had played left wing for the Johnstown Jets, the team that inspired the Chiefs. Ned told people the character wasn’t based solely on Goldthorpe but a compilation. Total bull, Goldie says: “That’s not even close to the truth.”

Indeed, Nancy herself later said as much when introducing Goldthorpe at a Newman Charities event: “When I first came to Johnstown, maybe even before, I had heard rumors of someone very intimidating…I never saw him, never saw a picture of him, but in my writer’s imagination, he took shape and became real…I created Ogie the ur-goon from this man’s reputation…the man who invaded my imagination long ago, Bill Goldthorpe!”

Goldthorpe didn’t get a chance to play himself in the movie Slap Shot, but he has a cult following nonetheless.

Courtesy of Liam Maguire and Bill Goldthorpe

Goldthorpe didn’t get the chance to play himself in the movie because of who he was. He tells the story of the night during the 1975-76 season when he played a game for the Broome County Dusters in Johnstown, a game Paul Newman’s brother had come to watch. Afterward, in the dressing room, Goldie got angry at a teammate who wouldn’t shut up about the way Goldie had gotten charged with assault for his part in a fight with fans. Goldie chucked a bottle of Coke at the teammate. It hit the wall, shattered and splattered its contents all over Newman’s brother, who happened to walk in at that moment. So Goldie wasn’t cast in the film. “They were more worried about how I was going to behave off the ice,” he said.

So while the movie transformed Steve and Jeff Carlson and Dave Hanson, who played the affable pugilistic Hanson brothers, into cult heroes – they made almost 90 public appearances annually and were sponsored by Budweiser – the man who inspired Ogie Ogilthorpe remained anonymous. Bitter, Goldie didn’t even bother to watch the movie for a dozen years. It wasn’t until 1989 that he finally saw Slap Shot, after his sister convinced him to view it while visiting her in Toronto. He was surprised how much he enjoyed it. “I never laughed so hard,” he said.

That took the edge off his bitterness. But the true healing began when he started getting invited to some of the promotional events. Around 2000, the rest of the cast started including him in golf tournaments and banquets anchored by the movie. He finally met Nancy Dowd herself in 2006 at the Newman Charities event. Dowd admitted to being a bit nervous beforehand that Goldie would live up to his nasty hype.

“But he was just incredibly nice and just a real gentleman,” she told the New York Times. “And when I read the tribute, he had tears in his eyes. Here was this guy who was the biggest goon alive, and he was so kind. It was a wonderful moment.”

And in that telling, Dowd put the finishing touches on Goldie’s reputation.