If you were a New York Rangers rooter in November 1954, you wouldn’t have wanted to be Allan Stanley.

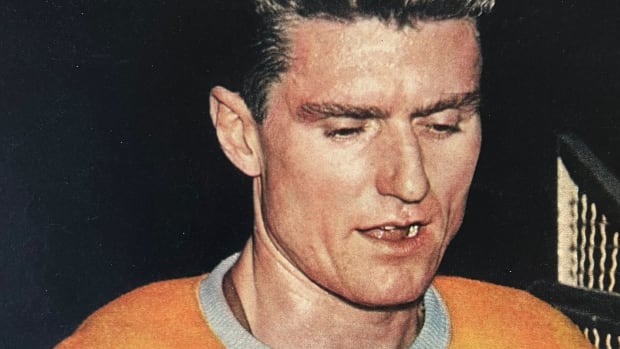

For four years, the handsome – when he had his teeth in – defenseman was ridiculed by Blueshirts fans like no player in the club’s long history. The hissing and moaning from the farthest reaches of the end balcony down to the costly arena seats was unremittingly insulting.

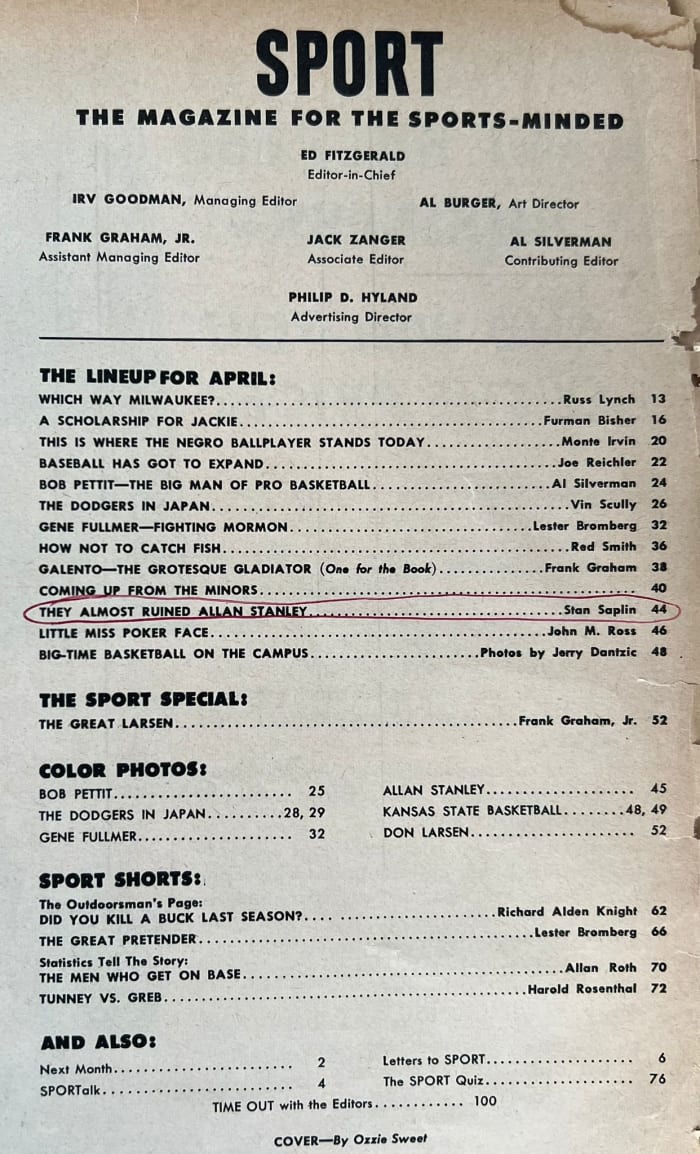

Writing in the April 1957 issue of Sport magazine – see pictured table of contents – New York Journal-American NHL beat man Stan Saplin wrote passionately about the victimized blue liner in a story titled, “They Almost Ruined Allan Stanley.”

“The gallery gods blasted him as an expensive patsy, called him ‘Sonja’ and almost drove him out of the league. Yet, somehow, he shook his rabbit ears in Boston,” the article said.

Saplin, who happened to be my mentor when I was breaking into the hockey writing business, had taken a personal interest in the hulking defender. After all, Stan was the Rangers publicist in 1947-48 at the time GM Frank Boucher obtained Allan from the AHL’s Providence Reds.

Boucher handed the AHL sextet cash, three pro players and the rights held by the Rangers to the services of an amateur. Saplin estimated that the value in cash and players ran between $60,000 and $70,000, an enormous price tag at that time.

“It was considered the largest deal ever for a minor leaguer in the history of the game,” wrote Saplin in the Sport magazine article. “He was known as ‘the $70,000 rookie.’ “

For a short time, the 22-year-old freshman was welcomed by the often harshly critical Gotham fans. The Rangers won five of their first seven games with him in the lineup.

Add to that the fact that ‘Big Allan,’ as he was originally labelled by the press, was a good-looking broth of a boy adorned with a Hollywood smile.

“But that smile turned upside-down once we started losing,” Saplin recalled. “The fans needed an outlet, though, for the bitterness that grew within them as Rangers failure piled upon failure.”

By hockey standards, Stanley was a defensive defenseman who took care of business in his own zone and was – wisely, I might add – content to catapult his forwards goalward with slick, accurate passes. But Rangers fans wanted more.

“For $70,000, they wanted me to go streaking down the ice with the puck,” Big Allan revealed to Saplin in the Sport confessional. “That’s fine for cheers. But a man on the other team will check you, right in your own zone, and there they are, back on the attack again. So I’d get a few cheers, they might score on us and we might lose. What good is that?”

The many-faceted New York hockey media could not ignore the Stanley story, and the more Allan became the focus of the Blueshirts troubles, the more difficult it was for him to play his game.

With one seasonal exception.

During the 1949-50 campaign, the Rangers suddenly became a hot item. They not only made the playoffs but knocked off favored Montreal in the opening round and then faced the Red Wings in the Stanley Cup final.

Although the Ringling Bros. & Barnum & Bailey Circus had forced the Rangers out of their Madison Square Garden home, the Blueshirts pushed the Detroiters to seven games – plus double overtime – before bowing to the Motor City sextet.

Unquestionably in that particular post-season, Stanley played his best hockey yet as a New Yorker. But when the 1950-51 Rangers slumped again, the fans got on Stanley’s case, and the antipathy increased with every loss.

Saplin: “The fans booed Stanley incessantly and screamed ‘Ya bum, ya!’ and shouted other select phrases. They hung signs from the front of the balcony, a tradition at Garden hockey games, some of them reading, ‘Stanley Is a Bum.’ Some said flatly, ‘Stanley Must Go.’ “

When the boobirds called him “Sonja,” they were linking Allan with Sonja Henie, the winsome Olympic figure skating star who had become a hit at Garden ice shows.

“The fans wanted no dainty figure skaters who reminded them of Miss Henie on their hockey team,” Saplin noted.

More as a benevolent gesture than any other, GM Boucher began removing Stanley from his lineup for home games. Finally, on the day before

Thanksgiving 1954, Allan and forward Nick Mickoski were dealt to the Chicago Black Hawks for defenseman Bill Gadsby and forward Pete Conacher.

(As assistant Rangers’ publicist at the time, I delivered the trade release to all the Manhattan newspapers that morning before Thanksgiving. I was thrilled to death to make those rounds, although I felt very sorry for Allan Stanley.)

“He was chased out of town,” added Saplin. “Out of New York City by the people who paid to see him play. The fans got rid of him. They booed him out, literally.”

In time, Chicago sold him to the Boston Bruins where his game approached all-star status. Eventually, ‘Big Allan’ wound up wearing the royal blue and white of the Maple Leafs. In Toronto garb, the man who couldn’t please the Rangers rooters became a hero in Maple Leaf Gardens on Carlton and Church Streets.

He was a prime reason Punch Imlach’s Leafs – between 1962 and 1967 – would win four Stanley Cups. And guess what? Allan Stanley, who played so well for that second Toronto dynasty, was eventually voted into the Hockey Hall of Fame.

For ‘Big Allan,’ unquestionably, the supreme irony of all took place one night after the much-maligned defender returned to the Garden. On this occasion – a happiest fella was Stanley – he was voted a star after playing an outstanding game against the Rangers.

Following the contest, Stanley dressed and exited on the 49th Street side of the Garden. He began walking down the street toward Broadway when a New York fan excitedly approached him with a lamentable critique.

“You didn’t play that way when you were with us,” the Rangers fan moaned in dismay.

“Yes I did,” Stanley sadly concluded. “Yes, I did.”

Just a final note to say that Saplin’s magazine piece remains to this day one of my all-time favorites. As for the ending anecdote, it still makes me feel awfully sad. I knew ‘Big Allan’ well, back to our Rangers days together. He was the salt of the earth; only the New York fans didn’t get it.