Could history repeat itself?

That was the hope expressed by the Rangers high command in the 1945-46 season – and for good reason.

The club’s first great line – Hall of Famers Bill Cook, Bun Cook and Frank Boucher – brought New York its first Stanley Cup in 1928. Now, in 1946, the Blueshirts thought they had a new trio that could repeat the feat. It was called the Atomic Line and, if nothing else, it held promise. But first, a bit of history is in order.

From 1942 through 1945, no NHL team’s roster was more decimated by enlistments in the Second World War than the Rangers.

The New Yorkers finished first in the 1941-42 season during which Uncle Sam entered the conflict. Then, one by one, the Blueshirts replaced their sweaters with Canadian and U.S Army khakis.

From the 1942-43 season until the end of the war, the Rangers continually missed the playoffs, and by a lot, too. But peacetime promised a new era for GM Lester Patrick and coach Frank Boucher. The boys, at last, were coming home.

“We were hoping that our stars from 1942 could return and play great again,” said Boucher. “But we also knew that many would have lost their hockey legs and have to be replaced. That’s why we were counting on our farm system.”

The Rangers had minor league and junior teams in New Haven (AHL), St. Paul (USHL), New York Rovers (EAHL), Verdun (Quebec Junior) and Guelph (Ontario Junior).

“What surprised us were the kids on our hometown (Rovers) team,” said Boucher. “They were tearing up the Eastern (Amateur) Hockey League like nobody’s business. They sometimes drew bigger crowds than our Rangers.”

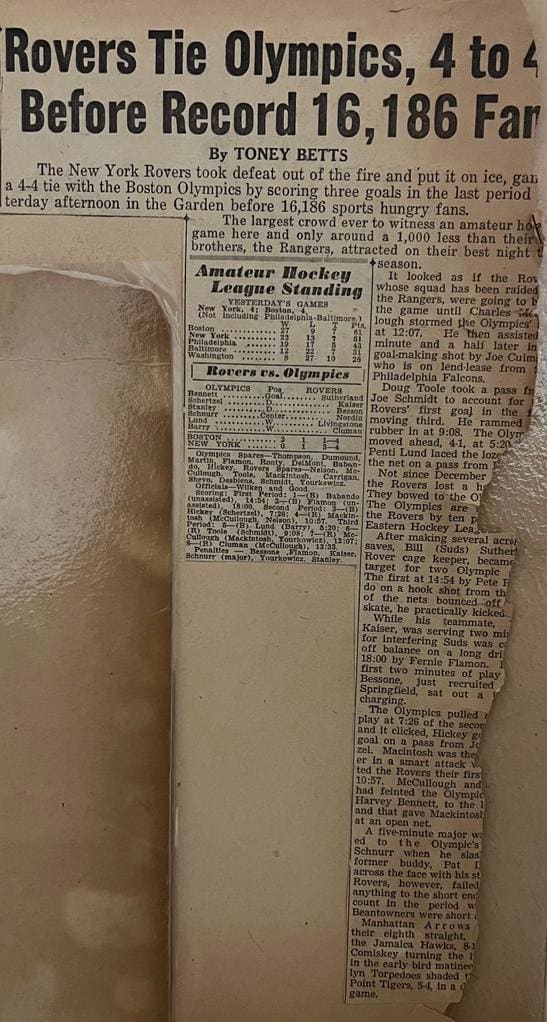

From my original scrapbook, I found proof positive of that. A headline in the New York Daily Mirror shouted, “Rovers Tie Olympics, 4 To 4 Before Record 16,186 Fans.”

Writing in The Mirror, Toney Betts called it “The largest crowd ever to watch a hockey game here.” And a good reason for that was the Rovers’ hot trio that featured center Cal Gardner, right wing Rene Trudell and left wing Church Russell.

Each learned their hockey in the Greater Winnipeg area and simultaneously arrived at New York’s training camp in the fall of 1945. From the outset, they fit like perfectly meshed gears.

“Rene was from my hometown (Transcona, Man.) and Church was from Winnipeg,” Gardner recalled in an interview I conducted with him. “Originally, our line was to be rounded out by Gus Schwartz on the left side, but he got hurt so they put Rene in his place.

“Russell, Trudell and I clicked immediately, and we started the 1945-46 season as the top line with the Rovers. Remember, this was right after the war, and everybody had memories of the atomic bomb in their heads. With that in mind some reporter nicknamed the three of us the Atomic Line.”

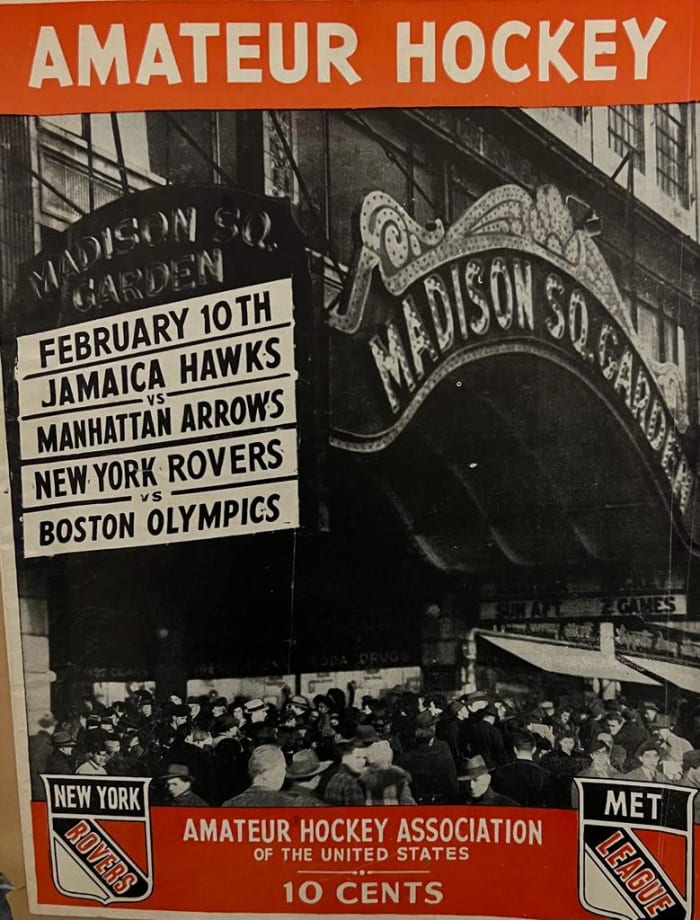

At age 13 in 1945, I attended every Rover game as part of the Sunday afternoon double-headers at the old Madison Square Garden on Eighth Avenue, just off Times Square. A Met League game began at 1:30 p.m. followed at 3:30 p.m. by the EAHL match and – it should be noted here – the Rovers were not amateurs. They didn’t earn a lot of dough, but they did get paid.

One of the many things I loved about those matches was that for a dime, I could get one of the best programs – anywhere, any time – in hockey at the Rover games. As you can see from the photo here, the program featured the old MSG marquee on the cover and a feature on the Atomic Line written by Sam B. Gunst on the lineup page.

While Gardner, Russell and Trudell were lighting red bulbs up and down the EAHL, the Rangers were struggling. The first-place stars from 1942 had mostly wilted, and the Rangers were hellbent for another missed playoffs.

Gardner: “Boucher felt he had to do something to help his club, and what he did was unprecedented in the NHL as far as I know. Instead of promoting me, or Church or Rene, Frank moved our entire line up to the Rangers.

“It was late in the (1945-46) season so we only got into 16 or so games. But, still, the Atomic Line going from the Eastern League to The Show in one leap was big stuff.”

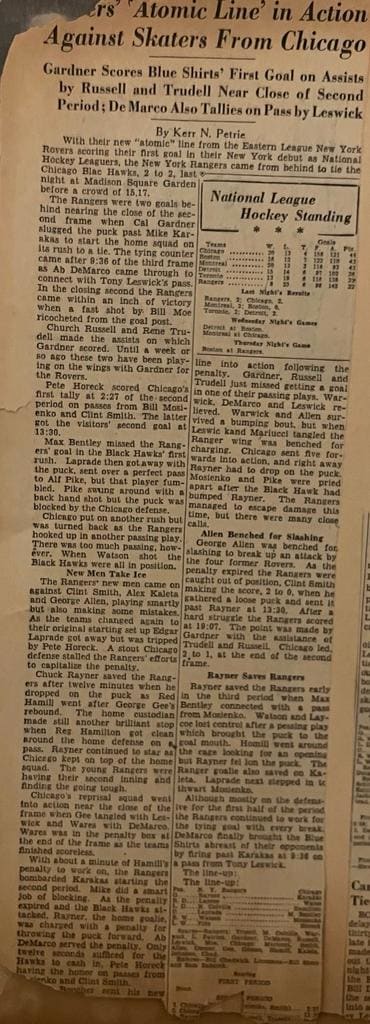

They made their NHL debut at Madison Square Garden late in the 1945-46 season against the Chicago Black Hawks. I actually found a frayed clipping of the story from the New York Herald-Tribune, authored by veteran reporter Kerr N. Petrie.

The headline was easy to read: “Rangers Atomic Line In Action Against Skaters From Chicago.” The subhead was very descriptive: “Gardner scores Blue Shirts’ first goal on assists by Russell and Trudell near close of second period: De Marco also tallies on pass from Leswick.”

I recall that Gardner – nicknamed ‘Ginger’ because of his reddish hair – was the best of the bunch and tallied eight goals and two assists in his first 16 games, which was not too bad at the time.

“I decided to keep them together as a unit to start the next (1946-47) season,” said Boucher. “It still was too soon to tell how good they’d be as an NHL line.”

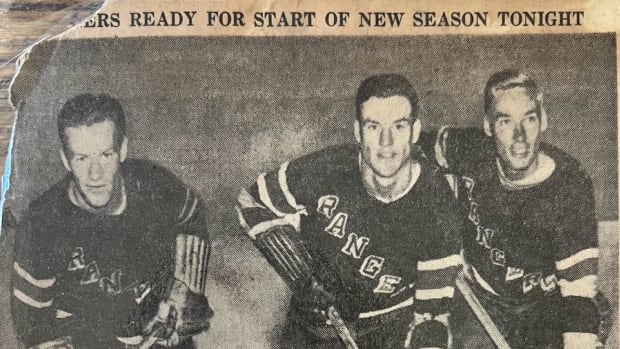

But the New York sports editors couldn’t wait. On the day of the home opener, The New York Times plastered a picture (see feature photo) of the trio on its lead sports page. The headline read: “Rangers Ready For Start Of New Season Tonight.”

Gardner: “Boucher kept our line together, and we played the entire 1946-47 season as a unit. That gave management enough time to decide what to do with us. The original novelty of the promotion had long ago worn off.”

Russell, who had dazzled as a Rover, couldn’t handle the rougher NHL and wound up with Cleveland in the AHL. Rene stayed with the big club, but since he was seven years older than Gardner, his days were numbered as well.

By the end of the 1947-48 season, Gardner had developed into a gritty, hard-nosed center who drew attention from Maple Leafs boss Conn Smythe. When Toronto captain Syl Apps retired after his club had won its second straight Cup in the spring of 1948, Smythe had to replace him.

“Smythe decided that of all the NHL centers, I was the one he wanted most of all,”

Gardner remembered. “Conn swung a deal with Boucher that sent me to the Maple Leafs. I had big skates to fill taking Syl’s place.”

Cal never would be the Hall of Famer like Apps was, but he helped Toronto to Stanley Cups in 1949 and again in 1951 before finishing his 12-year NHL career with Boston in 1957.

“Cal was a good player for us,” Boucher concluded, “but any hopes we had that the Atomic Line would be anything like Bill and Bun Cook – along with me – was just a sweet dream.”

Or, to put it in air force parlance, the Rangers Atomic Line was a dud.