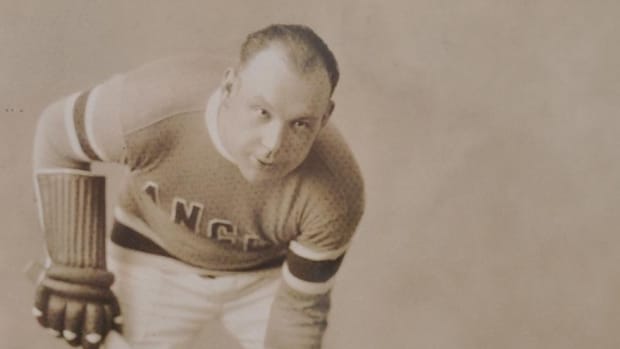

The family of Taffy Abel is hoping to see the NHL recognize the former New York Rangers and Chicago Blackhawks standout for what he was, the first.

As his family asserts, Taffy Abel was not only the first Indigenous person to compete in the NHL, but he was also the athlete to break the NHL’s color barrier when he stepped on the ice with the New York Rangers in 1926.

“If the NHL seriously wants to attract more BIPOC fans and grow their fanbase, they should show some respect and rightfully honor ‘the first’ BIPOC and Indigenous hockey player, Taffy Abel,” George Jones, Taffy Abel’s nephew, told The Hockey News, referring to the NHL’s recently released diversity & inclusion report.

Abel made his NHL debut on Nov. 16, 1926, decades before other racialized NHL players who have been recognized for breaking barriers including Larry Kwong, Willie O’Ree and Fred Sasakamoose.

A year later in 1927-28, Abel helped the Rangers win a Stanley Cup. In the final year of his eight-season, 333-game NHL career, Abel won his second Stanley Cup, this time as a member of the Chicago Blackhawks.

Before his NHL career, Abel broke another barrier as the first Indigenous hockey player ever to compete at the Winter Olympics. He served as the flag bearer for the United States and captained the Americans to a silver medal at the 1924 Olympics where he scored 15 goals in just five games.

In part, Abel has not been recognized in the same way as other trailblazers because he, and his family, concealed his identity for the entirety of his Olympic and NHL career.

They feared he would endure a similar fate to other racialized athletes and have his hockey dreams ended by racism.

It started in his youth when Abel’s parents hid his Ojibwe identity as a member of the Chippewa Nation. Abel passed as white, and his parents feared their son would be taken to a residential boarding school system as part of the ongoing cultural genocide committed against Indigenous peoples in both Canada and the United States.

“He played and passed as a white man in the Olympics and in the NHL,” explained Jones. “He passed as a white guy, not living his Native American heritage, but because of discrimination at the time againt Native Americans, and because of the residential boarding school system that pulled Indigenous kids right out of their homes, the decision to pass as a white person was made.”

Inducted into the United States Hockey Hall of Fame in 1973, Abel has received recognition from the hockey world for his on-ice play. But as Jones says, it’s time to have Abel seen as “the person who should solely be credited with breaking the NHL color barrier.”

In a step toward this, Abel was recognized by the United States National Archives this year in an exhibit titled All American: The Power of Sports alongside modern-day Indigenous hockey player T.J. Oshie as Indigenous trailblazers in USA hockey.

With the discussion of social change and racial equity ongoing in the NHL, George Jones believes the NHL’s unwillingness to recognize Taffy Abel’s Indigenous identity shows how far the work still must come.

“While progress has been made by the NHL, there is much more work to be done in the social justice area for Indigenous persons,” said Jones. “The lived experiences and future experiences of NHL players, fans, and employees who identify as Black, Indigenous, and People of Color need to see real changes being made versus just some window dressing or performative changes.”

It’s a call to action that Jones hopes will soon result in recognizing his uncle, Taffy Abel, as the NHL’s first Indigenous hockey player, and as the person who officially broke the NHL’s color barrier in 1926.